Tropical forests like the Amazon lock away vast amounts of carbon, but that carbon is not equally distributed. The largest 1% of trees store half of the carbon in these forests, and release it back into the atmosphere after they die. Unfortunately, tropical trees are dying at increasing rates, and giant trees are likely at risk, too — which could be a huge problem for climate change.

With a $1.45 million grant from the National Science Foundation, forest ecologist Evan Gora from Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies is co-leading a new project that will combine drone surveys and on-the-ground observations to investigate the deaths of large tropical trees. Named Gigante, the tree forensics project will monitor an unprecedented 7,500 hectares of tropical forest — about 29 square miles, or 14,000 American football fields — across three continents over the next three years.

“We know the largest trees in tropical forests disproportionately influence the future of our planet's climate,” explained Gora. “The deaths of those trees are really the dominant contribution they make to changing our planet's climate. So the goal of our project is to answer when, where, and why do these giant trees die, so that we can start managing forests appropriately and helping them adapt to future conditions.”

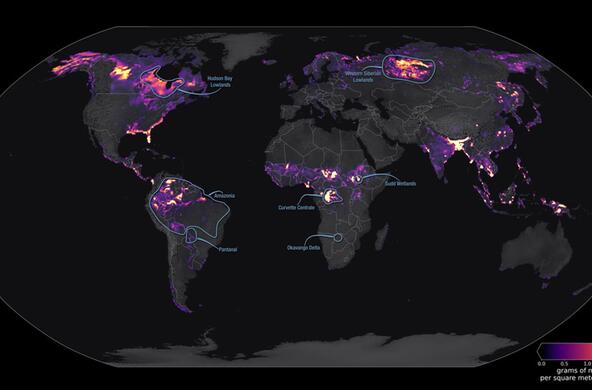

Adriane Esquivel-Muelbert co-leads the project at the University of Birmingham in the UK with additional funding from the UK’s Natural Environment Research Council. She and Gora will be working closely with scientists and technicians based locally at field sites in Panama, Brazil, Gabon, and Malaysia. Together with several institutions, including Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia, Universidade do Estado de Mato Grosso, Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, and the University of Leeds, the team will work to train early career scientists.

The researchers define giant trees as those with a trunk diameter of 50 centimeters or larger, which is about the width of a large pizza. While that may not sound very impressive, these trees comprise the largest 1% in the forest, with the vast majority of tropical trees being quite small and spindly. Over hundreds or thousands of years, the largest giants can grow up to 10 feet in diameter and reach heights of up to 330 feet.

Standing near one of these giant trees is like something from a fairy tale, said Esquivel-Muelbert. “The giant seems to be able to touch the sky. It makes you reflect on time and how much that tree has been through and how many other lives it has influenced, hosted, fed…. It takes a very long time for a tree to get to be a giant, so losing them means losing hundreds of years of carbon and all the connections and diversity built around it.”

Climate change is thought to be behind the recent rise in mortality for tropical trees, but the exact mechanisms are not yet clear. Until now, it has been difficult to investigate the deaths of giant tropical trees because they are rare and long-lived. Scientists have traditionally studied forests in plots the size of a hectare or smaller, but a plot of that size would contain so few giant trees — and even fewer that would die during the study — that it has been impossible to make out clear trends of giant tree death.

The Gigante team will overcome this barrier with the help of drones. Every month, the drones will fly over 1500 hectares of forest at each of the five research sites, mapping the canopy’s 3D structure and photosynthetic activity in order to spot when a giant tree is ailing. An on-the-ground team will then be deployed to search for clues as to the cause of death or damage. The researchers expect to be able to determine the cause of death for about 10,000 trees over the three-year project, compared to at most 360 for a traditional plot-based study.

Leading suspects in giant tree deaths are wind, lightning, drought, and disease — factors that are all changing along with the global climate. To differentiate between the potential culprits, the team will be recording lightning strikes and weather conditions, including rainfall, humidity, temperature, light intensity, vapor pressure, wind speed, and wind direction. The on-the-ground field team will gather other evidence. Uprooting and snapping, for example, indicate wind damage, while crown dieback may signal water stress. The dominant causes of death may turn out to be different at different sites.

Understanding the drivers of tree death and how they will change with global warming has big implications for forest management and reforestation efforts, said Gora. The project’s results could help foresters focus on species that will be best adapted to future conditions.

“We want to provide the knowledge so that if you want to reforest today, you're planting the species that will become the big, healthy trees 100 years from now, rather than just a random selection of species that may be doomed in that location 100 years from now,” Gora explained.

With a clearer picture of what’s killing giant tropical trees, and how quickly, the researchers can also calculate what these trends could imply for carbon storage across the tropics, both now and in the future. The project and its data — which will be open-source — will help to protect tropical forests and their crucial contributions to the carbon budget.

“While we know that environmental change threatens to increase tropical forest carbon release to the atmosphere, we still don’t know precisely how much, where, or why,” said Jason West, program director at the National Science Foundation. “This project is an exciting opportunity to combine new technologies, sophisticated models, and experienced field teams around the world to collect data on the death of large tropical trees and integrate that knowledge into predictions. The work will expand our limited understanding of the causes of large tree mortality, whether by drought, lightning, wind or disease, while also providing training opportunities for students and researchers across an international network, thus building capacity for the next generation of scientists.”