| May 1: Caterpillars Raining Down | May 8: Settling Down After Moving On |

| May 16: Can I See Your ID? | May 22: “Have you ever seen the rain, coming down on a sunny day?” |

| May 30: A Party for the Ages | June 12: The Beginning of the End? |

| June 19: The Dangers of Just Hanging Out | June 26: A Sigh of Re-leaf |

| July 11: Going, Going, (Almost) Gone! | August 26: Looking Back, Looking Ahead |

During the summer of 2023, spongy moth caterpillars caused severe defoliation of oak trees in parts of Southeastern New York. Questions and concerns about the likelihood and impacts of additional damage this coming year have prompted us to share our observations on spongy moth activity in the Cary forests during the 2024 season. Our 2000-acre research campus in Millbrook, New York is about 70% forested, and dominated by oak, hickory, maple, hemlock, and white pine trees. Major outbreaks have been observed periodically at Cary with peak emergences in 1980, 1992, and 2023. It remains to be seen if the spongy moth population will increase more this year or if it will collapse due to pathogens and stress from food shortages.

Background of the spongy moth

The spongy moth (Lymantria dispar dispar) is an introduced insect accidentally released in Massachusetts in 1869. Formerly known as gypsy moths, spongy moths have slowly spread across the Northeast. Larval stages (caterpillars) feed on a wide variety of trees, but oaks are the preferred food source. During periodic outbreaks, the insect can completely defoliate large areas of forests, and may severely damage shade and ornamental woody plants. Caterpillar droppings (frass) can significantly deter outdoor enjoyment during severe outbreaks.

Spongy moth populations rise and fall based on disease and predator pressures, with outbreaks occurring about every 10 years in New York. Cary Institute scientists have been studying the spongy moth since the early 1980s, and have unraveled some of the interrelationships between the moth, mouse populations, acorn abundance, and moth pathogens.

During 2022, spongy moth density in parts of Southeastern NY caused noticeable defoliation. Severe and more widespread damage occurred during 2023. Abundant egg masses were visible in our area during the winter of 2023–2024. It remains to be seen if this insect’s population will continue to build and cause more severe defoliation this year, or if disease will cause it to collapse.

Spongy moth observations from the Cary forests

May 1, 2024: Caterpillars Raining Down

We have been keeping an eye on the spongy moth egg masses overwintering at Cary Institute so that we could note when things start happening this spring. The time has arrived! Spongy moth caterpillars (first instar larvae) were seen hatching at the beginning of the week of April 29. The translucent bodies of the newly hatched insects quickly turned black while they remained clustered around the egg mass from which they emerged. Within a day, larvae were seen ballooning from their original hatching site, catching the wind with the silken threads they produced. I first noticed these migrating juveniles on my car. Later, they appeared on the sides of buildings. Now, every forest walk in outbreak areas may leave you with a hitchhiking caterpillar or two.

The insects hatched in synchrony with the appearance of leaves on several oak species, their favorite foods. These small larvae will try to make their way to the upper portions of their host tree, where they will begin feeding on the tender new leaves. Feeding damage at first appears as small holes in the leaf tissue. Later, as they molt into larger instars, their feeding will remove sections of the leaf until pieces fall to the ground or they consume all but the veins. Spongy moths will remain as caterpillars for about seven weeks, going through five (males) or six (females) molts before pupating and then turning into adult moths.

May 8, 2024: Settling Down After Moving On

Phenology: Hatching of egg masses is complete; 1st Instar larvae have ballooned to food sources and have begun feeding. Molt into the 2nd instar larval stage is imminent.

The word is out! Spongy moths were the talked-about nature phenomenon in our region last week as people became aware of the emergence of this invasive forest pest. Local news outlets, social media, and blogs took notice and sounded the alarm. Egg hatch and larval dispersal caught peoples’ attention, as did reports of skin irritation from contact with the insects’ tiny hairs. I caught myself taking a second look at my poison ivy-caused rash, just in case it might have been the result of this burgeoning pestilence.

During years when the spongy moth population is small, most newly hatched caterpillars crawl up into their host trees and begin feeding. In outbreak years like the current one, caterpillars may sense competition and possible food shortages to come. Or, they might recognize they hatched on a less-than-ideal food source. We don’t know why but when populations are large, many spongy moth caterpillars use silken thread to disperse from their hatch sites. The tiny caterpillars hang in the air waiting for sufficient wind to break their thread and carry them off to another location. This type of “ballooning” dispersal is common in moth species where the adult female cannot fly, including spongy moths. Perhaps this is a way for offspring to compensate for the limited dispersal opportunities of their parent.

Dispersing spongy moth caterpillars have no control over where the wind takes them. As we saw this week, many land in unsuitable places where their fates remain doubtful. Every possible surface (car, building, lawn furniture, posts, railings, and people) got a dose of these dispersing larvae; they even complicated activities like walking the dog. At the end of each walk, both dog and I had to be picked clean of the little black hitchhikers before the caterpillars crawled deeper and started me scratching.

Egg hatch appears to have finished, and the subsequent wind dispersal of the tiny caterpillars has slowed or even stopped. Larvae that fail to find a suitable plant will soon be dead, but more than enough lucky ones found a new host tree and have begun feeding. Shot-hole damage is already common on many oak leaves.

Soft-bodied parts of caterpillars grow larger as they feed, but the insects cannot change the size of their head capsule, one of the limited portions of their body covered with a hard exoskeleton. To continue growing, these caterpillars must shed their skins (a process called molting) allowing the head capsule to be replaced with a larger one. Some recently hatched caterpillars look ready to molt; you can spot this when their soft body grows wider than their heads and their bodies lighten in color to a characteristic greasy appearance. The next stage (2nd instars) has not yet been seen but should appear very soon. Larval stages are distinguished by a combination of head capsule size and color characteristics (see Identifying spongy moth early larval instars)

We have seen a number of news articles and social media posts that mistake other insects for spongy moths. Next week we will dive into the identification of this insect and its local look-alikes.

May 16, 2024: Can I See Your ID?

Phenology: Egg hatch appears to be completed. Both 1st and 2nd instar larvae are present and feeding in the tree canopies. Damaged leaves are visible, but the holes are still small.

This week I will compare spongy moth caterpillars to local look-alikes. I will also highlight the importance of native caterpillars as wildlife food, particularly for migrating songbirds who are arriving this time of year.

Right now, at least three species of hairy caterpillar larvae may be present and significantly damaging hardwood leaves in our region. All vary slightly in appearance depending on which instar you are looking at (early instars of all species are little, hairy, black caterpillars; older, larger life stages are easier to identify as different species). For an excellent visual, visit this Michigan State University Extension Bulletin.

1st instar spongy moth (Lymantria dispar dispar) larvae have black heads and bodies. Irregularly shaped yellow dots may be visible on the backs of 2nd instars; these dots are transformed into thin broken yellow lines in older larvae. By the 4th instar, the head is yellow and black, while the back of the body sports pairs of blue and red spots. Spongy moth caterpillars do not gather in webbed nests, but crawl singly into the tree canopy to feed. They congregate in resting locations at the base of trees during the day (unless there are many, when they tend to stay up in the canopy).

Eastern tent caterpillars (Malacosoma americanum) are native insects that make communal silken tents filled with many caterpillars and their droppings. These insects have a dark head and a narrow solid light-colored stripe down the center of their backs. Small blue dots may be visible on both sides. Eastern tent caterpillars are common this year in our area feeding on cherries, apples, and crabapples. This species prefers to feed on trees growing in full sun, presumably because leaves on such trees are more nutritious. Although distressing to see, healthy trees may withstand several years of total defoliation without long-term detrimental effects.

Forest tent caterpillars (Malacosoma disstria) are another species that may gather in large groups and can do significant damage to oaks and other native forest trees. They have bluish heads and sides and a central row of light-colored markings down their backs. Many references describe these markings as being in the shape of “keyholes”. Forest tent caterpillars do not make communal silken tents, but build silken mats under leaves and on the tree bark where they gather when not feeding. Like spongy moths, they feed on several tree species, particularly oaks and maples.

These are only three of the estimated 1,500+ Lepidoptera (butterfly and moth) species found in New York State. Only 20 or so species of eastern forest Lepidoptera reach densities that can result in the defoliation of large acreages. Most native forest-dwelling insects play important roles in those communities, notably as food for baby birds. Some ecologists believe that the spring migration of songbirds evolved because of the wealth of insects, particularly caterpillars, that appeared annually in temperate regions. The timing of bird migration seems linked with the timing of the emergence of new plant tissue and the many insects that feed on it. Most of our songbirds, regardless of what the adult eats, will feed their young on soft-bodied insects.

A quick look at the understory leaves of oaks in the Cary forest this week revealed a smorgasbord of inchworms and other caterpillars that serve as the primary food source for soon-to-hatch forest songbird babies. When we reduce the amount of vegetation available for insects (as when deer overbrowsing eliminates the natural understory) or we reduce the diversity of plant species (by killing off some with introduced plants, forest pests, and pathogens), we reduce the amount of insect food available for other wildlife. We can do much better to alleviate the impacts of too many deer and invasive pests and pathogens. Most important is to stop the spread of new pests before they arrive. Visit Tree Smart Trade to learn about this issue and what you can do to help.

For more on the importance of caterpillars to birds, visit Nature's Best Hope: Conservation that Starts in Your Yard, a Cary lecture with ecologist Doug Tallamy.

May 22, 2024: “Have you ever seen the rain, coming down on a sunny day?”

Phenology: Egg hatch is finished. Most caterpillars have reached 2nd or just started 3rd instar stages, although smaller 1st instars are still readily found. The rate of leaf damage from feeding caterpillars is increasing and frass (caterpillar poop) and leaf parts (greenfall) are raining down.

Creedence Clearwater Revival’s song “Have You Ever Seen The Rain?” has been stuck in my head. Supposedly, the title/chorus was a metaphor for going through difficult times. Right now, it is difficult to watch legions of caterpillars (mostly spongy moths, but also other species) consuming the leaves of woody plants in our forests and yards. A walk under an oak canopy becomes a gauntlet, zig-zagging past caterpillars suspended in mid-air on silken threads. Inevitably, caterpillars and leaf parts get on you as you walk. The spongy moth is a rather messy eater!

This year, the aforementioned song might also be taken as a metaphor for the caterpillar frass, which is also raining down around us on sunny (and cloudy) days. Stand under the forest canopy in an outbreak area and you can hear the frass hitting surfaces all around you. Stop, close your eyes, and listen; it sounds like a gentle rain.

Park your car under a tree, even for just a few hours, and you will return to a coating of tiny frass pellets on its surface. A real shower creates a brown, messy goop that must be cleaned off the windshield before turning on the wipers. Forget to clean, and you have a mess that requires a hose to get you back on the road.

All that caterpillar poop is a big deal to us humans. We don wide-brimmed hats, long-sleeved shirts, and long pants to avoid being covered with it (remember to keep your mouth closed when you look up!). It is also a very big deal to our forests. Disturbances - like pest outbreaks - can result in a loss of nutrients from forest ecosystems. About 20 years ago, Cary scientists investigated the impacts of spongy moth defoliation on forest nitrogen, an essential nutrient for tree growth. Trees take up available forms of nitrogen from the soil and carefully conserve this precious commodity. In years with normal (i.e. limited) insect damage, deciduous trees in the Cary forests reabsorb about 70% of the nitrogen in their leaves before dropping them in fall. In spongy moth defoliation years, only about 23% of the nitrogen in leaves gets reabsorbed back into the plant. Much of the leaf nitrogen goes to the forest floor in the frass rain, along with some nitrogen trapped in small bits of greenfall when the caterpillars cut leaves and drop them.

Eventually, the insects die and the nitrogen in their bodies that came from the leaves in the trees also goes to the forest floor. A revelation from the Cary research was that although spongy moth defoliation is a major disturbance, it primarily causes nitrogen to be redistributed and not lost from the forest ecosystem. The nitrogen that falls to the forest floor gets taken up mostly by microbes or is trapped in organic materials in the soil. Trees may recapture small amounts of that nitrogen in the year of defoliation, helping to fuel the new flush of leaf growth once spongy moths finish feeding; the rest of the nitrogen will be available to the trees in subsequent years. Very little nitrogen is actually lost from the forest.

A single year’s defoliation is not likely to kill a healthy deciduous tree but does reduce its store of essential nitrogen. Next week we will look at how other stressors combined with spongy moth defoliation can dramatically alter forest communities.

May 30, 2024: A Party for the Ages

Phenology: Caterpillar stages range from 3rd to 6th instars with most in the 4th and 5th instars. Caterpillar frass (poop) and greenfall (pieces of cut leaves) continue to rain down. Oak canopy defoliation ranges from 50-100% within the forest.

A wide range of spongy moth caterpillar sizes are now found in the Cary forests. Why are so many different stages present?

Many different caterpillar stages can be found due to variation in the timing of spongy moth hatch and differences in their growth and development rates. The warmer it is, the faster insect development progresses. Female spongy moths laid egg masses in a wide range of sites at the end of last summer, each with its own microclimate. This spring, egg masses in warmer sites hatched before egg masses in cooler sites.

Once hatched, some lucky caterpillars found themselves on oak trees and had easy access to newly unfurled, high-quality leaves – which fueled fast growth and development. The less fortunate hatched on trees of lower quality, less nutritious food, and still decided to dig in. They grew and developed more slowly. Others dispersed from unsuitable hatch sites, and by doing so, delayed starting to feed for a day or two.

Timing of hatch, food quality, and food availability all contribute to why we see the many different caterpillar stages all at the same time. So what does this mean for the forest, and us? Feeding and defoliation will occur over a longer period of time than if all the caterpillars had developed in perfect synchrony on the best quality food. It means we will have to tolerate seeing caterpillars for longer. Unless a disease starts to spread rapidly through the spongy moth population, defoliation won’t end until all the remaining caterpillars stop feeding and pupate, preparing them to turn into adults and mate.

For the first time since bud-break in spring, oak canopies actually got smaller during the last week, with losses to spongy moth caterpillars exceeding leaf development. Some oaks are now completely defoliated. Hungry caterpillars will migrate laterally across the branches of leafless trees to those nearby, or drop down from the canopy and look for food in the understory, or walk over the ground and climb up another tree. Expect to find them feeding on less desirable species as oak leaves disappear.

Check your ornamental woody plants for incoming migrations of caterpillars. It is probably too late to apply BTK sprays, but frequent hand-picking, or removal from burlap bands placed around trunks, can reduce damage if you have the time to do this daily. Wear gloves or use a brush to sweep them into warm soapy water.

Avoid using sticky bands unless you cover them with cages to prevent the accidental capture of birds and small mammals as many try to eat trapped insects. If you have important trees in your yard that are defoliated, your best option to help them at this stage is to ensure they get adequate water. If we get a drought during summer be sure to mulch and water them.

June 12, 2024: The Beginning of the End?

Phenology: Caterpillars have reached 5th and 6th instar stages. The first pupae were found today and appeared since trees were last examined on June 8th. The rain of frass (poop) and greenfall (pieces of cut leaves) have stopped as oak canopy defoliation approaches 100%. Sick and dead caterpillars are common on tree trunks and understory vegetation.

Dead and dying spongy moth caterpillars are showing up all across the Cary forests. Is this the beginning of the expected and hoped-for population crash? It is too early to know for sure, but it could well be.

Three factors are currently killing the caterpillars - let’s review them.

Many spongy moth caterpillars have been infected and killed by the fungal pathogen Entomophaga maimaga. This disease was first introduced to control spongy moths in 1910, but failed to establish. Reintroduced again in the 1980s, it is now widespread in the Northeastern US. When the weather is favorable (damp and warm but not hot for too many days), and the spongy moth population is moderate to high, the fungus can have multiple generations – killing many caterpillars. Fungus-killed caterpillars look like dried-out, head-down caterpillar mummies. Based on what we have seen, this is a very good year for the fungus and a bad year for the spongy moth.

We are also seeing many caterpillars killed by Nuclear Polyhedrosis Virus (NPV), another introduced pathogen that occurs throughout our region. When the spongy moth populations are low, NPV kills a few caterpillars each year; in most cases, infection is sub-lethal. During boom years, when populations are large, NPV can be the primary cause of death for late-instar caterpillars. This is because caterpillars suffer from increased stress as food and resting space become limited, reducing their immunity to NPV, and allowing a viral pandemic to run through the population. NPV-killed caterpillars typically hang down as soggy, bad-smelling, inverted v’s. This year looks like a viral pandemic in progress.

With oak defoliation approaching 100%, some of the caterpillar deaths we are seeing are likely caused by a shortage of high-quality food. When the best food runs out, caterpillars attempt to migrate across the canopy or drop into the understory searching for better fare. A diet of poorer-quality food slows caterpillars' growth and, if food is inadequate, they die from starvation. In the interim, limited food and/or poor quality food puts those same caterpillars under stress, which then makes them more susceptible to dying from the virus. Inadequate food is a lose/lose proposition for a caterpillar. So in this kind of situation if the virus does not get you, then starvation will.

Dr. Clive Jones, a Senior Scientist at Cary Institute, thinks the magnitude of caterpillar deaths we are seeing will result in a significantly lower spongy moth population next year at Cary. Will the population crash to the point where it is not a problem in our area? It might if sufficient caterpillars die before pupating – the causes of mortality described here only act on the caterpillar stage. However, other players can attack and kill spongy moth pupae and eggs and may further reduce the pest population. That is a story for next week!

June 19, 2024: The Dangers of Just Hanging Out

Phenology: Live caterpillars are difficult to find; dead ones can be seen throughout the forest. Most surviving spongy moths have reached the pupal stage. Defoliated trees have swollen buds or newly unfolding leaves as the canopy consumed by the caterpillars begins to regrow.

As a teenager (yes, it was decades ago), it was standard practice to meet and “hang out”. Although frowned upon by some as wasting time, I recall transformational growth occurred on occasion. Spongy moths at Cary are also hanging around undergoing their own transformational process called metamorphosis. A pupa (singular of pupae) is the life stage that transitions caterpillars into adult moths. Spongy moth pupae are dark brown, hairy, and usually attached to tree bark by a few haphazard strands of silk. Female pupae are much larger than male pupae. Many pupae I see this year are next to the former caterpillar’s abandoned exoskeleton from which it emerged. Touch a live pupa and it does a little waggle dance, likely a response to try and ward off a predator or parasitoid (the first one I found was “dancing” to repel a parasitic wasp trying to lay an egg on it).

Spongy moths remain as pupae for 10-14 days. Because male caterpillars go through one less molt (5 instars) than females (6 instars), males typically pupate first and emerge or “eclose” as adults before females. I expect to start seeing male moths flying at Cary the week of June 23 (female moths do not fly). Females get mated by males as they eclose; egg masses should begin to appear thereafter.

I’m finding very few pupae in Cary’s forests. Many caterpillars died before they could transition. The lucky ones likely pupated in hard-to-find places like tree bark crevices. Pupating in sheltered locations is a strategy to avoid being eaten while you are fixed to one spot for many days. Some insect parasitoids (species of wasps or flies) lay a single egg near or inside a spongy moth pupa. The parasitoid egg hatches and its larva feeds on the living pupa, which eventually dies. Parasitoid populations at Cary have likely been growing over the last two years in response to the exploding numbers of spongy moths. There may now be many parasitoids hunting a smaller number of spongy moths; not a good scenario if you are a spongy moth pupa!

A variety of small mammals will also make a meal of spongy moth pupae. These include shrews, voles, chipmunks, and squirrels. White-footed mice are the most voracious small mammal predators of spongy moth pupae, and they are also the most abundant small mammal in our forests. These mice are as comfortable foraging on trees as on the ground. They prefer the larger female pupae but will eat both sexes. By preferring females, they can reduce the number of eggs laid, impacting spongy moth populations.

Mice can play a role in helping an outbreak collapse when mice are abundant and spongy moth pupal numbers are low, particularly after outbreaks have declined and the abundance of other natural enemies have waned. That may be what we will see this year. For decades, Cary researchers have tracked the rise and fall of mouse populations each year, and have studied the interrelationships between mice, oaks, acorns, spongy moths, and Lyme disease. Right now, white-footed mouse numbers are moderate (ca. 10 mice per acre) and rising. Again, more bad news if you are a spongy moth pupa.

We will likely end up with relatively few egg masses this year, thanks to the collapse of the spongy moth caterpillar population due to the fungus, virus, and starvation, followed by attacks of pupae by white-footed mice, other predators, and parasitoids. Eggs in the egg masses will likely be attacked by an increased egg parasitoid population built up over the last two years. It is also possible that the defoliation-induced lack of food means that those females that survive to lay egg masses will produce fewer eggs per egg mass.

At this point, it seems unlikely that the spongy moth will have much impact on Cary forests next year. We will have more insight on what to expect in 2025 in a couple of weeks when we see how many female pupae survive to lay egg masses and how large those egg masses are. Next week I will talk more about what is happening to all those defoliated trees.

References about spongy moth parasites and predators:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/247843911_Of_Mice_and_Mast

https://www.caryinstitute.org/science/research-projects/past-projects/acorn-connections

https://www.fs.usda.gov/nrs/pubs/gtr/gtr_nrs179.pdf

https://www.canr.msu.edu/uploads/files/e2700.pdf

June 26, 2024: A Sigh of Re-leaf

Phenology: Male spongy moth adults were first spotted at Cary on June 22. Shortly thereafter, on June 24, the first adult female moth was found laying eggs. Growth of new leaves is visible on many defoliated canopy and understory trees.

As I pass through Cary Institute’s oak woodlands, perhaps a dozen flying male spongy moths are visible from any spot where I stop. This is more moths than I expected given the massive die-off of caterpillars we witnessed, but far less than the hundreds of flying moths we experienced last year. It remains to be seen how many females have survived to lay eggs, and how many eggs will hatch next year.

The re-leafing of the forest canopy above me is far more noticeable than the few fluttering moths. Within 3-4 weeks of being defoliated, healthy oaks and other deciduous trees will regrow their leaves and resume making and storing carbohydrates through the process of photosynthesis. While evergreen trees may be killed by a single spongy moth defoliation, deciduous trees can be defoliated two or even three years in a row and still recover. That is unless other stress factors come into play.

Flooding, drought, and spring frost can stress trees and lead to their decline and even death. Drought before or during years of spongy moth defoliation can be a major stress factor for oaks in the Eastern US. Environmental stressors also provide an opportunity for secondary pathogens and pests to gain the upper hand and cause tree decline. In our region, the most common pathogens that attack weakened oaks are Armillaria and Phytophthora fungi, which cause root or collar rots. These pathogens are always present but kept at bay by healthy trees' defenses. Drought can also make trees more attractive to insect pests. The two-lined chestnut borer (Agrilus bilineatus) is a native bark-boring insect most frequently associated with mortality of stressed oaks in the US.

Symptoms of tree decline and death do not show up until well after stress events have occurred. Oak mortality associated with Armillaria spp and two-lined chestnut borer usually occurs one to two years after a major drought. It can take up to three years for tree decline and death to show after back-to-back years of severe spongy moth defoliation. This spring we noticed an unusual number of oaks that failed to leaf out. Likely, the severe summer drought we experienced during 2022, followed by extensive defoliation by spongy moths during 2023, allowed secondary pests or pathogens to kill these weakened trees. The spongy moth defoliation in 2024 has weakened additional trees, possibly leading to further tree death over the next few years, particularly if more stress occurs, such as an extended drought this summer.

An upside is that trees most susceptible to spongy moth defoliation may not be the most vulnerable to subsequent decline and death. Spongy moth defoliation occurs most frequently in exposed ridges; these areas have shown limited post-outbreak tree mortality. Trees on these sites are adapted to frequent stress from shallow soils with less water and nutrients. They are able to shift more carbohydrates into storage, compared to the rapid growth of trees on better sites. Because they have more reserves, trees on poor sites may be better defended against secondary pests and pathogens than trees that get defoliated on rich, well-watered sites.

Encouraging the overall health of trees is the best way to prevent them from declining and possibly dying from environmental and biotic stresses. Consider watering spongy moth-defoliated high-value landscape trees if you have sufficient water supplies. Apply the equivalent of about 1” of water out to the tree’s drip line (edge of foliage) each week if adequate rainfall does not arrive. Mulching under the tree conserves water, eliminates turf that competes for water and nutrients, and prevents careless mowers and string trimmers from damaging the trunk. About 3” of mulch is all that is needed. A thicker mulch layer may suffocate the tree’s roots. Never pile mulch or soil directly around the trunk. Consider getting advice from a certified arborist regarding pruning and fertilizing trees that show dying branch tips or other signs of decline.

Trees that fail to grow new leaves this summer or show significant canopy dieback over the next couple of years are unlikely to recover and should be removed if they pose a hazard. The stress caused by spongy moths should continue to decline and, hopefully, outbreaks like this will be infrequent. Giving treasured trees a little extra TLC this year may pay valuable dividends in helping them recover and prosper.

July 11, 2024: Going, Going, (Almost) Gone!

Phenology: Adult female spongy moths have finished egg-laying and most have completed their life cycle and died. Only a few female moths have been observed and the small number of egg masses they produced often appear undersized and irregularly shaped. Defoliated trees continue to grow new leaves, but at variable rates. How long it will take for a full reflush and the extent to which trees will fully reflush remains to be seen.

The spongy moth population at Cary has dramatically collapsed. Earlier this year, we removed the egg masses laid in 2023 within our reach from the bark of 10 oak trees. We found 750 masses on those trunks. This week, we visited those same 10 trees and found only three egg masses, a 250-fold decrease from last year’s number. Not only did this year’s female moths produce fewer masses, they are smaller than usual. Because food started to run out when caterpillars were in the 5th instar, few females likely made it through the 6th instar. Those that did were in poorer condition with fewer eggs to lay. This all points to a smaller number of caterpillars hatching next year.

Egg parasitoids will likely further reduce the number of viable eggs. Small black wasps (Ooencyrtus kuvanae) that lay their eggs in spongy moth egg masses have increased over the last few years as spongy moth numbers exploded. Now they are competing for a limited number of spongy moth egg masses. Smaller egg masses are more vulnerable to these parasitic wasps. Their short ovipositors can not reach deep into larger egg masses, leaving some eggs safe. The share of eggs parasitized could jump from less than 10% to 30-40% per mass. This will not be a good year to be a spongy moth egg!

Cary Ecologist Clive Jones predicts that spongy moth populations at Cary will continue to collapse over the next year or two due to egg parasitoids and parasites of larvae, whose numbers have also increased over time. He estimated that we started 2024 with 2-4 thousand egg masses per acre (5-10K per hectare) and now have only 40-200 new masses per acre (100-500 per hectare). When the population drops to about 20 egg masses per acre (50 per hectare) or lower, predation on pupae by white-footed mice will be enough to keep the moth under control.

We can’t predict how long it will be before another spongy moth outbreak occurs at Cary. Long-term monitoring tells us that it will start after a major mouse population crash due to a failure of acorn production. Outbreaks average about a decade apart, but this can vary; at Cary, our last spongy moth outbreak was 30 years ago. The biological and environmental factors that cause spongy moth outbreaks and their collapse are similar throughout the northeast, but their timing and magnitude vary from location to location. This accounts for differences in spongy moth numbers seen elsewhere in the Hudson Valley compared to our experience this year at Cary. The pattern of population boom and bust events should be similar even if the timing may vary by a year or two. High spongy moth populations that failed to crash this year are likely to collapse next season.

In the final blog post in two weeks, we will look at the state of tree recovery from spongy moth defoliation, revisit what we learned, and – since you have just experienced what an introduced pest can do to a forest – suggest how you can help stem the tide of introduced insect pests and pathogens into our forests. Stay tuned!

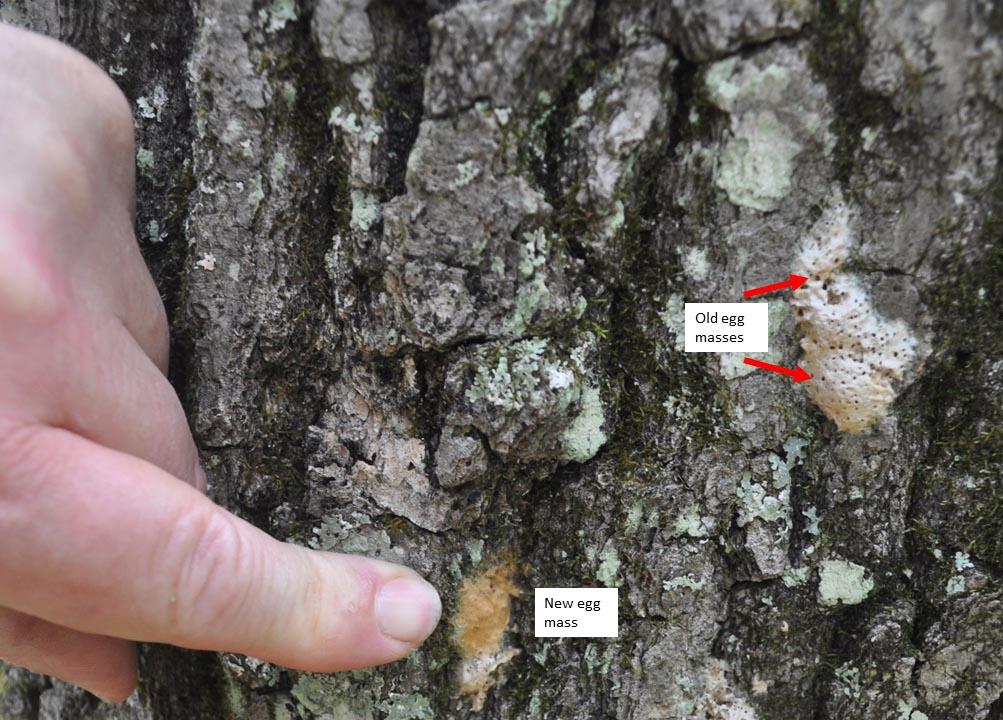

(Aging spongy moth egg masses: If deposited in a protected location, egg masses may remain visible for years, long after their eggs have hatched. With a little practice, it is easy to distinguish viable new masses from those hatched in previous years. Compared with new masses, old ones are somewhat bleached in color, and may be covered with tiny holes where parasitic wasps emerged. Old masses are also softer to the touch and your finger seems to compress them further – hence the name “spongy moth”, or as it is called in Quebec, “éponge”, which is where the US got the new name from).

August 26, 2024: Looking Back, Looking Ahead

Phenology: The 2024 Spongy moth season is over. Adult female spongy moths finished egg-laying and died. The spongy moth larval population crashed before pupation. Few adult female moths emerged, resulting in few egg masses for next season. The area of re-flushed leaves on defoliated trees was highly variable, but generally not as large as the leaf area originally eaten by caterpillars. Powdery mildew leaf infections can be seen on re-flushed leaves of defoliated understory white oaks and chestnut oaks.

In this final entry for this season, we will revisit what we saw, look at the state of tree recovery from spongy moth defoliation, and, since we have just experienced what an introduced pest can do, suggest ways to stem the tide of introduced forest pests and pathogens in the future.

Looking back

Several factors allowed the spongy moth population at Cary to build up to a high going into 2024.

- By eating moth pupae, the white-footed mouse population was able to keep the spongy moth in check since the last outbreak collapsed in the mid-1990’s. However, a very low acorn crop in 2020 caused a major collapse of the mouse population in 2021 and the start of the moth outbreak.

- Since the moth population had been low for a long time, there were few other predators and parasites to help prevent the moth population from rising rapidly in 2021 and again in 2022, and again in 2023 when partial defoliation was first observed.

- Weather conditions in those 3 years were not particularly favorable for the fungal disease of spongy moth larvae – Entomophaga maimaiga; spring and early summer was not wet enough for the fungus to kill more than a few larvae. So by the end of summer 2023, oak trees at Cary Institute were covered with spongy moth egg masses – a harbinger of the coming insect Armageddon.

The predicted spongy moth caterpillar explosion happened in May 2024, with egg hatch being accompanied by the dispersal of huge numbers of larvae ballooning on silk, going everywhere, and causing many people in the mid-Hudson region to experience skin irritation and rashes. Caterpillar feeding then more or less fully defoliated trees (mostly oaks) in the canopy and understory of Cary forests, accompanied by a rain of frass (caterpillar poop) and greenfall (bits of cut but uneaten leaves). It was a wet spring and early summer and the weather, in combination with the large number of larvae led to an epidemic of the fungus that killed many of the caterpillars.

At the same time, as food began to run out, caterpillars became stressed and succumbed to the Nuclear Polyhedrosis Virus, or just starved to death. Most caterpillars died before they could pupate and metamorphose into adult moths. Because female caterpillars take longer to develop, more of them succumbed to disease and starvation before pupation. Female pupae also had the additional disadvantage of being larger and more sought out by hungry white-footed mice whose population was now at moderate levels. As a result, while we saw some male moths emerge, very few female moths made it; so very few egg masses were produced.

What about the poor trees? Most have grown back many leaves, but not to the full size that was consumed by hordes of hungry caterpillars. New leaf expansion seems to have stopped, and stressed trees will likely drop their leaves earlier than healthy ones. Certain stands have many oak seedlings with severe powdery mildew infections, mostly on re-flushed leaves. The fungi that cause these infections (there can be several species) target developing leaves. Weather conditions are usually unfavorable for the fungus when leaves first appear in spring. However, the warm, humid conditions during re-flushing were ideal for the fungus. It seems to be more of a problem for trees at Cary in the white oak group (mostly northern white oak and chestnut oak), but less so in the red oak group (northern red oak, black oak).

What's ahead

We are confident that the limited number of egg masses produced in 2024, combined with predation and parasitism of eggs, caterpillars and pupae from natural enemies that have built up in numbers in the interim, will cause the spongy moth population to continue to decline in our forests over the next few years. We may be hard-pressed to find any for a while and there will not be any defoliation until the next outbreak peak sometime in the future. Whew! Of course, your results may differ, depending on what stage in the boom-and-bust spongy moth cycle was reached at your site this year; but don’t fret – all outbreaks eventually come to a crashing end.

We also expect that because the populations of other predators and parasites – most notably the egg parasitoid, Ooencyrtus kuvanae – have now increased in response to the moth increase, that egg hatch and larval survival will be low in 2025; the moth population will continue to decline; and there will be no defoliation until the next outbreak some years from now.

Our concern now is how the damage done to trees by spongy moths, in combination with the weather, will impact tree survival. In 2022, a severe summer drought killed some trees outright and left others weakened. That drought was then followed by two consecutive years of spongy moth defoliation that will have reduced the reserves stored by the trees; opening the possibility of significant tree mortality and potential future susceptibility to other stresses such as drought and pathogens that attack weakened trees. A big test will be how many trees leaf out in the spring of 2025 – those that do not are done for. Others may look sickly (e.g., some canopy dieback) but may recover, and some may continue to decline for several years before dying. The effects of the last three years will take time to play out and will depend on the upcoming growing seasons, with drought adding substantially to mortality risk. Homeowners should pay attention to ornamental and specimen trees that look weak and “baby them along” when they can. Consulting a certified arborist is a good way to begin.

The most common pathogens that attack weakened oaks in our area are Armillaria and Phytophthora fungi, which cause root or collar rots. These pathogens are always present but kept at bay by healthy trees' defenses that in turn, depend on stored reserves. We have had adequate rainfall recently, so drought stress is unlikely to further harm trees this year. However, weakened trees can also succumb to infections from these fungi when too much rain arrives. Some sunshine and less humid weather would be welcome by the trees as well as humans!

Damage and decline will not be limited to canopy trees that form the forest “roof”. Some small oak seedlings that were defoliated now have severe powdery mildew infections on their re-flushed leaves. This can cause seedlings to lose their leaves early, reducing the stored reserves they have to grow next spring. Powdery mildew infections also weaken the ability of buds to survive cold temperatures. Some infected buds may die if this winter is a cold one. This could reduce next year’s growth and increase how many years it takes for seedlings to grow out of reach of hungry herbivores like white-tailed deer. Changes in the growth rate and survival of oak seedlings as a result of spongy moth activity, fungal infections, and munching deer could conceivably alter which tree species dominate future Cary forests. At the same time, any canopy trees that do die will allow more light to reach the understory, helping saplings to grow faster. Yeah, this ecology stuff is interwoven and complicated!

Let’s stem the tide

A lot has changed as a result of the accidental release of spongy moth in North America more than 150 years ago. We hope this blog has helped illustrate the damaging impacts introduced forest pests can have. Spongy moths are a reminder that fixing the problem after the pest arrives is either very hard or impossible, and invariably has substantial costs. The best way to protect our landscape plantings, ornamentals, shade trees, and forests is to prevent the next invasive pest or pathogen from getting here. We can all contribute to improving this situation by asking our elected officials to take meaningful steps to prevent new introductions. Most new forest pests arrive in wood packing materials or plants imported from other countries. A team of scientists led by the late Gary Lovett at Cary Institute studied the problem of invasive forest pests and found that existing trade regulations and protocols do not adequately protect our forests. They outlined five innovative priority actions that can markedly help stem the tide of new invasions if implemented. Go to Tree-SMART Trade to learn more about these priorities and how you can help, so that in the future you and your children do not have to experience the kind of spring and summer we all just went through due to some other pest!

You can expect one more blog entry in the spring of 2025 to examine how the trees have fared and offer some final insights. Best wishes and thanks for tuning in this year!

Are you concerned about the spongy moth in your area? Check out the Resources section.

Resources

Insect defoliation and nitrogen cycling in forests

Identifying spongy moth early larval instars

What you need to know about spongy moths: a Q&A with Ecologist Clive Jones

The Spongy Moth in Our Yards and Forests

A fascinating and comprehensive look at this pest’s life history, ecology, and forest impacts.