In response to Scott Pruitt’s efforts to lighten environmental regulations, I have blogged before about the importance of protecting small streams, see: Waters of the United States. Now, new research reinforces the role of small streams in cleansing runoff waters of nitrogen, phosphorus and other pollutants that are problematic for water quality and harmful to coastal fisheries. Small streams that have frequent fluctuations in depth and turbulent flow as they pass over obstacles in the stream channel are particularly effective in removing nitrate from runoff water.

Excessive concentrations of nitrate in streams stem from the runoff from agricultural fields that are fertilized, from leaking septic fields, and from human sewage that is incompletely treated in waste-water facilities. By some counts, the level of nitrate in waters of the United States is more than twice as high as might naturally occur.

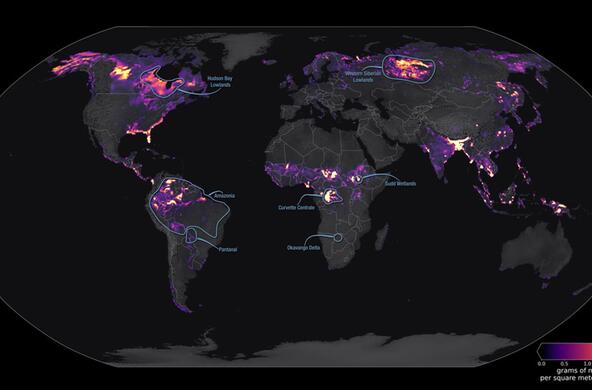

Thankfully, nitrate is a raw material for the metabolism of certain bacteria, known as denitrifiers that convert nitrate to nitrogen gas that is released to the atmosphere. These bacteria function in areas without oxygen (anoxic), such as stream sediments and floodplain soils (when they are flooded). Nitrate is delivered to these bacteria most efficiently when the streamflow is turbulent, which mixes fresh water into the anoxic zones at the greatest rates. Denitrification in floodplain soils occurs at the greatest rates when they are alternately wet and dry, as a result of fluctuations in streamflow. Denitrification is also important in seasonally flooded wetlands, known as vernal pools. (See: Save the Wet Spot). One recent study suggests that small wetlands are five times more effective at removing dissolved nitrogen from streamwaters compared to various direct human interventions.

Overall, the removal of nitrate from streamwater is greater in small streams, which have a greater amount of flooded sediments and floodplain soils per unit of stream length. One study documented 100 times greater nitrate removal in small streams compared to the Mississippi River, which often carries excessive nitrate loads to the Gulf of Mexico.

As a supplement to the Clean Water Act, the Clean Water Rule was specifically designed to protect small streams and wetlands connected to them. Of course, land developers find its provisions bothersome, since the regulations reduce the land area that can be repurposed. (From the beginning, farmers were exempt from its provisions). Bowing to these pressures, the EPA is recommending abandonment of the Clean Water Rule, despite the plethora of science showing the value of small wetlands to wildlife and water quality.

When small streams are filled, rerouted, channelized and otherwise destroyed, they are gone forever. The legacy of Scott Pruitt will be that the services provided by small streams will be lost and just as the nation must cope with increasing problems in providing clean water to all citizens.

References

Alexander, R.B., R.A. Smith and G.E. Schwarz. 2000. Effect of stream channel size on the delivery of nitrogen to the Gulf of Mexico. Nature 403: 758-761.

Cheng, F.Y. and N.B. Basu. 2017. Biogeochemical hotspots: Role of small water bodies in landscape nutrient processing. Water Resources Research doi: 10.1002/2016WR020102

Grant, S.B., M. Azizian, P. Cook, F. Boano and M.A. Rippy. 2018. Factoring stream turbulence into global assessments of nitrogen pollution. Science 359: 1266-1269.

Hansen, A.T., C.L. Dolph, E. Foufoula-Georgiou, and J.C. Finlay. 2018. Contribution of wetlands to nitrate removal at the watershed scale. Nature GeoScience 11: 127-132.

Peterson, B.J. and 14 others. 2001. Control of nitrogen export from watersheds by headwater streams. Science 292: 86-90.

Shuai, P., M.B. Cardenas, P.S.K. Knappett, P.C. Bennett, and B.T. Neilson. 2017. Denitrification in the banks of fluctuating rivers: The effects of river stage amplitude, sediment hydraulic conductivity and dispersivity, and ambient groundwater flow. Water Resources Research doi: 10.1002/2017WR020610